Is the teaching of beginning reading so mysterious and complicated that we still do not know for sure how to proceed? Such is the conclusion of Robert C. Aukerman after he reviewed 165 different approaches to beginning reading. He says that he suspects that some of the 165 different approaches may be more effective than others, but at this time we cannot know which ones, because it appears “next to impossible” to apply “adequate research techniques” to the evaluation of reading methods. He says that until we can understand and apply the psychology of learning to the methods of research, we must be content with our “primitive means” and go ahead and do “the best we can.” He gives one note of optimism: “We certainly can do better than we are doing at present.”1

That we “can do better than we are doing at present” seems to be an understatement, considering the growing numbers of Americans who cannot read or write properly. “Today, a staggering 23 million Americans—1 in 5 adults—lack the reading and writing abilities needed to handle the minimal demands of daily living. An additional 30 million are only marginally capable of being productive workers…. Demographers say the number of illiterates is steadily mounting, swelled by 1 million school dropouts a year.”2 The National Assessment of Education Progress survey published in 1976 says that in 1975, 35 percent of the nation’s fourth graders, 37 of the eighth graders, and 23 percent of the twelfth graders could not read.3 The Adult Performance Level study of 1975 shows that only “46.1 percent of the population between 18 and 65 were fully proficient and fluent readers. As you can see, the illiterates plus the slow readers are now a majority of the U.S. population.”4

Considering these statistics, there can be little doubt that our schools need to do a better job of teaching reading. But Professor Aukerman’s conclusions about what one must do in order to try to do better must be extremely disheartening to those who do not know the “secret” of teaching reading. He says that a “surprising number of ‘others’ have entered the field of reading from such areas as business, linguistics, speech, hearing, sociology, technology, languages, homemaking, television, psychology, physical therapy, audio-visual materials, programming, statistics, medicine, and optometry,” and that we would do well to heed what all of them have to say. He thinks that it is necessary that we have knowledge of all of the new approaches, and that “each new approach deserves a chance to prove itself under reasonable research conditions and in normal classroom environments.” We must make “every effort to explore the good in each approach and give each a chance to prove itself in our own hands.” If we do otherwise, we “may be rejecting the very messiah for whom we have so long been watching and waiting.”5 Earlier, in his introduction, Professor Aukerman set the stage for his reviews by saying that any findings presented in his book “as evidence that one approach to beginning reading is superior to another, or that any approach is effectual as a means of helping children learn to read are, at best, educated guesses.”6 These are discouraging words, if true. Aukerman’s conclusions indicate that even if one were able to personally experiment with all known approaches to reading and listen to the ideas of experts from every field imaginable, one still would be able only to guess at how to go about teaching reading.

But is this pessimism justified? Let us first point out that although Aukerman refers to 165 approaches, most of those approaches generally fit into one of two basic approaches to beginning reading: the whole word approach or the phonics approach. Within these two systems there are, of course, variations which may be difficult to evaluate, but the central elements of these two approaches not only can be evaluated but already have been. It is unconscionable and silly to pretend that we still do not know which of these two basic approaches is superior. The earlier whole-word (look-and-say or sight-reading) method has been thoroughly discredited and shown to be the major cause of the reading problems in America today (see the overwhelming evidence in the books by Blumenfeld, Chall, Flesch, and Terman and Walcutt listed at the end of this article). But now we have a modified whole-word approach that came into being after Rudolph Flesch and others made such a strong case for phonics. The whole-word establishment decided to camouflage their old approach to make it appear that they are now teaching phonics. In reality they are not. According to Aukerman, they are including some strands of phonics, but the phonics elements are only casually related to the whole-word approach which they still use.7 Flesch says, “In contrast to the phonics-first texts, which teach all of phonics; look-and-say materials teach only a small part…. By now I estimate that on the average they offer 20 to 25 percent of the phonic inventory….”8

This new whole-word approach has, among other things, been called “gradual phonics” because it spreads its few phonics elements out over several years. True phonics, in contrast, has been called “intensive phonics” because it teaches all of the main sound-symbol relationships intensively from the very beginning of reading instruction. Because of the “slick” promotion of this new method, many people may not realize that the method is still the whole-word (look-and-say or sight-reading) method. They may believe that since it has some phonics in it, it may now be all right. The intent of this article is to show why the whole-word (gradual-phonics) method should be scrapped, and intensive phonics put in its place.

- The whole-word (gradual-phonics) method cannot be an efficient method of teaching beginning reading because the main assumption upon which the entire system depends is erroneous. This method is predicated on the belief that a reader perceives new words as wholes (i.e., as shapes or outlines).9 The devotees of this method assume that because adult readers see words as wholes and do not always have to analyze the parts, a beginning reader must learn new words as wholes. Walcutt, Lamport, and McCracken dispute that assumption.

Rapid adult readers can register whole phrases or short sentences at a glimpse because, and only because, they have perfect images of the words already stored in their brains…. But the adult reader sees all the letters (never a mere shape or outline) because he has learned the words as left-to-right sequences of letters, and he understands them that way. Now he sees them as “whole-word units.” But he did not learn them that way.10

In 1844, Samuel Stillman Greene wrote an excellent essay refuting the whole-word approach, which at that time was being vigorously advocated by Horace Mann. Mr. Mann, attempting to prove that printed words should be learned as whole objects, gave this example: “When we wish to give to a child the idea of a new animal, we do not present successively the different parts of it—an eye, an ear, the nose, the mouth, the body, or a leg; but we present the whole animal, as one object.”11 Professor Greene showed the flaws in Mann’s thinking with this reply:

…The illustration drawn from the animal, or a tree which is more commonly given, fails, we think, to meet all that is required in teaching a child to read. Grant, that he does not, in learning to distinguish a tree from a rock, or any other dissimilar object, form his idea of it by inspecting the parts separately, and then by combining trunk, bark, branches, twigs, leaves, and blossoms. In learning to read, however, he is to distinguish between objects which resemble each other, and in many instances, very closely, as in the case of the words, hand, band; now, mow; form, from; and scores of others. To make the illustration good, it would be necessary to place the child in a forest, containing some seventy thousand trees, made up of various genera, species, and varieties, among which were found many to be distinguished only by the slightest differences. Or, if it will suit the case any better, let him be placed in a grove, containing seven hundred trees, having, as before, strong resemblances; if, then, this general survey of each of them, as a whole object, will enable him to distinguishthem rapidly from each other, whatever may be their size, or the order in which he may cast his eyes upon them, we will acknowledge the aptness of the illustration.12

The reader can easily see how Greene’s analogy applies to the perception of words. One can tell the difference between a word written on a page and a fly walking across the page without examining the parts of either one: he can perceive each of them as wholes. But one can reliably and consistently distinguish one word from another only by being able to recognize the parts that make up each word.

Now, here is one final proof that we do not perceive words as wholes when learning to read. Everyone knows that our language is an alphabetic language; that is, the written words are made up of symbols that represent the sounds of audible words. If we can determine how we perceive audible words (whether as wholes or as individual sounds), we should be able to infer that we perceive written words (which represent the audible words) in the same way. After all, in both instances the brain is doing the same work of translation: in the first instance through the ear; in the second, through the eye. Recent scientific studies give conclusive answers to this question.

Workers at the Haskins Laboratories in New Haven, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sweden’s Royal Institute of Technology and elsewhere have shown that the speech signal is a complex of acoustic units; brief segments bounded by momentary pauses or peaks in intensity….

Experimental results confirm that in the perception of speech we are ordinarily aware of discrete phonemic categories rather than of the continuous variation in each acoustic parameter: we perceive speech categorically….

…categorization occurs because a child is born with perceptual mechanisms that are tuned to the properties of speech. These mechanisms yield the forerunners of the phonemic categories that later will enable the child unthinkingly to convert the variable signal of speech into a series of phonemes and thence into words and meanings.13

There you have it. A human being perceives speech signals as separate sounds, and then converts the series of sounds into words.He does not perceive audible words as wholes. It should be clear that it would indeed be strange and unnatural if we do not perceive the written symbols of words in the same way that we perceive the audible sounds. Thus a system that makes children try to read by perceiving words as wholes must be viewed as grossly unnatural and pernicious.

- The intensive-phonics method has been proved successful everywhere it has been used. Many experienced teachers and administrators testify to its effectiveness. Mary L. Burkhardt, director of the Department of Reading (K-12), City School District Rochester, New York, tells about the tremendous results achieved when she got rid of the look-say and eclectic (combination phonics and sight-reading) programs and replaced them with intensive phonics programs.

When I entered the district in 1966, the student population was 40,000 (40 percent minority). Now it is 35,000 (57 percent minority). I am sure that you have often heard it said that the percentage of children who are minority influences the degree of reading failure in a given school or district. Reality is that whether children are “advantaged” or “disadvantaged,” black or white, rich or poor, does not have anything to do with how successfully children learn to read. Based on my professional experiences, such statements are only excuses for not teaching children to read….

…At that time, only look-say and eclectic programs (not phonics-first) were used in the school…. In spite of the teachers’ hard work and the children’s readiness and willingness to learn, children were having trouble learning to read. In fact, remedial readers were being generated in my school faster than I could remediate them.

Five years later (after replacing the old reading programs with three phonics-first programs). Rochester’s students are readers. Our students’ average reading performance is above grade level at grade one and at grade level in grades 2 through 6 as measured by the Metropolitan Reading Achievement Test. Please note that this test measures reading comprehension. This is a dramatic change from only five years ago when one of the major topics of conversation was the number of non-readers in our schools. Today, students automatically decode logically, systematically, and successfully. This enables them to use their energy to read for meaning and understanding, which of course is the ultimate purpose and joy of reading.14

At a teachers’ conference one year in Miami, Florida, I overheard a principal of a Christian school discussing reading with a friend who taught in another Christian school. The principal commented that students could not learn to read in kindergarten because they were not ready yet. The teacher replied, “How can you say that? I have taught five-year-old kindergarten for five years, and every year all of my students learn to read.” That pretty well ended the discussion. What could the principal say in view of such success? (The teacher, of course, was using an intensive-phonics program.)

I recently talked with the curriculum director of a large Christian day school about the effectiveness of their intensive-phonics program. She replied, “Our system simply does not produce any non-readers.”

Kathryn Diehl, author of Johnny Still Can’t Read—But You Can Teach Him at Home, says this:

I have seen enough excellent teachers of phonics systems in action to be in awe of them. They teach class after class in which no child reads below grade level, and the classes average two or three years above grade level. They have never seen a “dyslexic” child, nor produced a “learning disabled” or non-reader…. The one thing the sight-word advocates have never been able to prove is that children don’t learn to read with intensive phonics. They can’t prove it, because the evidence is over whelming that children can and do learn to read when properly taught with a good phonics system.15

[Note: There are of course dyslexic children, but not many. My first-grade teacher, with whom I talked recently, told me that in her forty-three years of teaching reading she had had no more than five dyslexics.]

If anyone doubts these personal experience stories, all he has to do to confirm their verity is to go to a school where intensive phonics is taught and ask to observe the children reading material they have never seen before.

- Rigorous research shows that intensive phonics is superior to gradual phonics. In 1965, Dr. Louis Gurren of New York University and Ann Hughes of the Reading Reform Foundation published a review of research which presented twenty-two comparisons between intensive phonics groups and gradual-phonics groups. Of the twenty-two comparisons, nineteen favored intensive phonics, three favored neither method, and none favored gradual phonics. Considering all the talk about meaning and comprehension by the gradual-phonics advocates, it is especially interesting that sixteen comparisons favored the intensive-phonics group as to comprehension and not one favored the gradual-phonics group. Gurren and Hughes’s overall conclusions are these:

- Rigorous controlled research clearly favors intensive teaching of all the main sound-symbol relationships, both vowel and consonant, from the start of formal reading instruction.

- Such teaching benefits comprehension as well as vocabulary and spelling.

- Phonetic groups are usually superior in grades 3 and above.16

In 1974, Dr. Robert Dykstra of the University of Minnesota published the results of his research concerning the best way to teach beginning reading. Here are his conclusions:

Reviewing the research comparing (1) phonic and look-say instructional programs, (2) intrinsic and systematic approaches to helping children learn the code, and (3) code-emphasis and meaning-emphasis basal programs leads to the conclusion that children get off to a faster start in reading if they are given early direct systematic instruction in the alphabetic code. The evidence clearly demonstrates that children who receive early intensive instruction in phonics develop superior word recognition skills in the early stages of reading and tend to maintain their superiority at least through the third grade. These same pupils tend to do somewhat better than pupils enrolled in meaning emphasis (delayed gradual phonics) programs in reading comprehension at the end of the first grade…. There is no evidence to justify the assertion that early instruction in the code brings about decreased reading speed. We can summarize the results of sixty years of research dealing with beginning reading instruction by stating that early systematic instruction in phonics provides the child with the skills necessary to become an independent reader at an earlier age than is likely if phonics instruction is delayed and less systematic. As a consequence of his early success in “learning to read,” the child can more quickly go about the job of “reading to learn.”17

In 1967, Dr. Jeanne S. Chall, director of the Reading Laboratory and professor of education at Harvard University, published Learning to Read: The Great Debate, which has since become a classic study on the best way to teach beginning reading. In 1983, she published an updated edition of the book, detailing the research from 1967-1981. In the 1983 edition, she says that the latest research even more strongly supports the conclusions she reached in 1967.18 Here are those conclusions:

My review of the research from the laboratory, the classroom, and the clinic points to the need for a correction in beginning reading instructional methods. Most school children in the United States are taught to read by what I have termed a meaning-emphasis method [gradual phonics]. Yet the research from 1912 to 1965 indicated that a code-emphasis method—i.e., one that views beginning reading as essentially different from mature reading and emphasizes learning of the printed code for the spoken language—produces better results, at least up to the point where sufficient evidence seems to be available, the end of the third grade.

The results are better, not only in terms of the mechanical aspects of literacy alone, as was once supposed, but also in terms of the ultimate goals of reading instruction-comprehension and possibly even speed of reading. The long existing fear that an initial code emphasis produces readers who do not read for meaning or with enjoyment is unfounded. On the contrary, the evidence indicates that better results in terms of reading for meaning are achieved with the programs that emphasize code at the start than with the programs that stress meaning at the beginning.19

- The whole-word (gradual-phonics) method is an ideal tool for those who are using the educational system for purposes other than that of achieving excellence in education. The proponents of gradual phonics constantly emphasize what they call “reading for meaning” or “thought-getting.” One might think that they are referring to the getting of precise meaning from the words on the printed page. Such is not usually the case. Walcutt, Lamport, and McCracken give insight on this subject in their review of a section of Edmund Burke Huey’s The Psychology and Pedagogy of Reading (1908). Huey’s “two assumptions were (1) that the meaning of a printed page was not exactly represented by its words and (2) that a good reader could get at the ideas without necessarily knowing or recognizing the words.”20 Huey says that it is all right if a “child substitutes words of his own for some that are on the page, provided that these express the meaning…. ”He stresses that we need to get away from the notion.

That to read is to say just what is on the page, instead of to think, each in his own way, the meaning that the page suggests.…It may even be necessary, if the reader is to really tell what the page suggests, to tell it in words that are somewhat variant; for reading is always of the nature of translation and, to be truthful, must be free…and until the insidious thought of reading as word-pronouncing is well worked out of our heads, it is well to place the emphasis strongly where it really belongs, on reading as thought-getting, independently of expression [i.e., the individual words].21

Huey’s theories are still influencing the whole-word advocates today. Professor Frank Smith, the “apostle of psycholinguistics,” is an example. He says that “meaning is not something that a reader or listener gets from language, but something that is brought tolanguage…. When we identify meaning in text, it is not necessary to identify individual words.”22

Not all of the whole-word (gradual-phonics) advocates will think that the quotations from Huey and Smith describe what they are trying to do when teaching reading for meaning: they may believe they are teaching the students to get meaning from the page. But the whole-word method itself necessitates the situations that the two men describe. For example, when a child who does not know phonics comes to a word he has not learned, he is encouraged to try to guess from the context what the word may be. When he does this, it is said that he “brings meaning to the page.” If he comes reasonably close to the meaning, he is to be commended, even though he may not have chosen the exact word on the page. This business of guessing at what “the page suggests” is indeed just what Professor Kenneth Goodman, senior author of the Scott, Foresman readers, calls it: “a psycholinguistic guessing game.” Goodman is the one who, in an interview with the New York Times, said that if a student substituted the word pony for the word horse he should not be corrected. “The child clearly understands the meaning,” he said. “This is what reading is all about.”23 Obviously, then, whenever the initial emphasis is placed upon meaning instead of upon identifying the exact words that are on the page, a student is implicitly learning that individual words are not important.

Individual words may not be important to “progressive” educators (for whom excellence in education has never been a goal), but the emphasis upon individual words has always been of paramount importance to Christian educators, who believe in the verbal inspiration of the Scriptures and in quality education. Orthodox Christians believe that God gave every word of Scripture, not just the thoughts. David Chilton, writing for the Institute of Christian Economics, reminds us that

one major difference between orthodox Christianity and paganism is the fact that Christianity is a linguistic religion: it stresses doctrine, content, the importance of linguistic communication; in short, the primacy of the Word. The Bible is a revelation in words, and calls for an intelligible …response…. 24

Christians therefore who are training young people to respond to Jesus’ command to “live by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God” (Matt. 4:4) should reject a system of reading that trains students to guess at words and to be content with approximate meanings.

Mario Pei in The Story of Language makes an incisive observation that reveals one of the reasons the “progressive” educators detest phonics and “book learning.”

When a written form is achieved, the result is generally greater stability in the spoken tongue. Many languages of primitive groups are unwritten and consequently highly fluctuating, with many dialects, a rapid rate of change, and an undetermined standardform. Similar high variability in the spoken language is to be observed in tongues like Chinese, in which the written symbol for the thought rather than for the sound still persists. An ideographic system of writing places little restraint upon the spoken language. A phonetic system constricts the spoken tongue into a mold, forces the speakers, to a certain extent, to follow the traditional orthography, rather than their own whimsical bent, and gives the rise to “correct” and “incorrect” forms of speech which, were the spoken language unrestrained by a written form, would be equally “correct” variants…. 25 (Emphasis added.)

If one uses the whole-word method, which treats phonetic words as if they were ideographs, one can get away from stability, from standards, from restraint, from traditional pronunciation, from traditional spelling, and from correct and incorrect forms of speech. Such freedom is delightful to the “progressives,” but not to Christians who see the importance of standards in all areas of life and thus are striving for excellence in education.

Samuel L. Blumenfeld in his book NEA: Trojan Horse in American Education makes it very clear why the whole-word method is not suitable for use by anyone whose goal is excellence in education. He contends that the progressive educators, who “got rid of traditional phonics and replaced it with the whole-word, look-say methods and text-books,” did so knowing that the whole-word method would lower the literacy rate in America. They wanted the literacy rate lowered because they knew that low literacy would make it easier for them to reach their goal of making America into a socialist society.26 Blumenfeld traces this subversion back to John Dewey.

To Dewy, the greatest enemy of socialism was the private consciousness that seeks knowledge in order to exercise its own individual judgment…. High literacy gave the individual the means to seek knowledge independently. To Dewey it created and sustained the individual system which was detrimental to the social spirit needed to build a socialist society.…What better way to undermine this independent individualism than by denying it the necessary tool for its development: high literacy…. Thus the goal was to produce inferior readers with inferior intelligence dependent on a socialist elite for guidance, wisdom, and control.27

It should be evident now that if one wishes to teach his students that individual words are not important, that freedom from standards is desirable, and that low literacy is acceptable because it promotes the goals of socialism, he should use the whole-word (gradual-phonics) approach. But if one wishes to promote high literacy, excellence in education, and individual responsibility, he should use the intensive-phonics approach.

At this time, some educators are recognizing the failure of the whole-word method and are trying to switch to intensive-phonics programs, but it is estimated by Rudolph Flesch and others that approximately 85 percent of America’s schools are still using the whole-word (gradual-phonics) method, many of them mistakenly thinking that they are teaching phonics. Further progress may be made in the public schools, but those attempting to change reading methods will have to overcome the fierce resistance of the liberal educational establishment in order to do so.

The situation in Christian schools is much better. Excellent intensive-phonics programs are available, and most Christian schools across the country are using them. Unfortunately, a few Christian educators have accepted uncritically the abortive system put forward by progressive educators. The Christian must be wary of every theory that comes from humanistic thought and must not accept anything that is contrary to Scripture and the purposes of Christian education. He must remember that if the rudiments (first principles) are wrong the methods that take their rise therefrom must of necessity be suspect. Colossians 2:8 says to “beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world.”

Samuel Blumenfeld in The Victims of “Dick and Jane” makes a discerning comment concerning the reading programs in private schools.

Most private schools, particularly the religious ones, where Biblical literacy is central, teach reading via phonics. But since many private schools recruit their teachers from the same pool of poorly trained professionals and use many of the same textbooks and materials found in the public schools, their academic standards may reflect more of the general culture than one might expect…. The quality of a private school’s reading program therefore really depends on the knowledge its trustees and principal may have of the literacy problem and its causes. It is this knowledge that can make the difference between a mediocre school and a superior school.28

Considering Blumenfeld’s statement and the information presented in this article, a suggestion seems to be in order. Examine your present system of teaching reading. If it is a gradual phonics (whole-word, look-say, sight-reading, eclectic) approach, get rid of it and replace it with a program that teaches phonics intensively from the beginning of reading instruction. Remember, all the religious teaching in the world cannot make up for the damage done by the use of wrong methods.

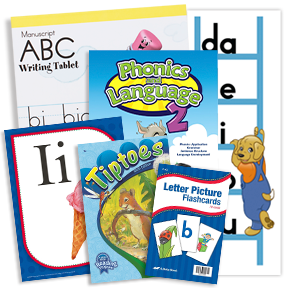

Abeka's six step approach to phonics works.

SHOP PHONICSFor Further Reading

Blumenfeld, Samuel L. NEA: Trojan Horse in American Education. Boise, Idaho: Paradigm Co., 1984.

. The New Illiterates—And How You Can Keep Your Child from Becoming One. New Rochelle, N.Y.: Arlington House, 1973.

Chall, Jeanne. Learning to Read: The Great Debate. Updated ed. New York: McGraw- Hill Co., 1983.

Flesch, Rudolph. Why Johnny Can’t Read—And What You Can Do about It. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1955.

. Why Johnny Still Can’t Read: A New Look at the Scandals of Our Schools. Foreword by Mary L. Burkhardt. New York: Harper and Row, 1981.

Gurren, Louise and Hughes, Ann. “Intensive Phonics vs. Gradual Phonics in Beginning Reading: A Review.” The Journal of Educational Research 58 (April 1965):339- 347.

Terman, Sibyl, and Walcutt, Charles C. Reading: Chaos and Cure. New York: McGraw- Hill Co., 1958.

Notes

1Robert C. Aukerman, Approaches to Beginning Reading, 2nd ed. (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1984), p.604. 2Stanley N. Wellborn, “Ahead: A Nation of Illiterates?” U.S. News and World Report, 17 May 1982, p. 53. 3Rudolph Flesch, Why Johnny Still Can’t Read: A New Look at the Scandal of Our Schools, with a Foreword by Mary C. Burkhardt (New York: Haper and Row, 1981), p. 62. 4Ibid., p. 63. 5Aukerman, Approaches to Beginning Reading, pp. 7, 606, 608. 6Ibid., p. 6. 7Ibid., pp. 322-23 8Flesch, Why Johhny Still Can’t Read, pp. 72, 75. 9Charles C. Walcutt, Joan Lamport, and Glenn McCraken, Teaching Reading: A Phonic/Linguistic Approach to Developmental Reading (New York: Macmillian Publishing Co., 1974), p. 30. 10Ibid., pp. 31-32. 11Samuel L. Blumenfeld, The New Illiterates—And How You Can Keep Your Child from Becoming One (New Rochelle, N.Y.: Arlington House, 1973), p. 340. 12Ibid., pp. 341-42. 13Peter D. Eimas, “The Perception of Speech in Early Infancy,” Scientific American, January 1985, pp. 46, 48-49. 14Mary L. Burkhardt, Foreword to Why Johnny Still Can’t Read, by Rudolph Flesch, pp. xiv-xv, xix-xx. 15Kathyrn Diehl and G. K. Hodenfield, Johnny Still Can’t Read—But You Teach Him at Home (New York: Cal Industries, 1979), pp. iii, 46. 16Louise Gurren and Ann Hughes, “Intensive Phonics vs. Gradual Phonics in Beginning Reading: A Review,” The Journal of Educational Research 58 (April 1965):339, 341, 344. 17Walcutt, Lamport, and McCracken, Teaching Reading, p. 397. 18Jeanne S. Chall, Learning to Read: The Great Debate, updated ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1983), p. 43. 19Ibid., p. 307. 20Walcutt, Lamport, and McCracken, Teaching Reading, p. 28. 21Ibid., pp. 28-29. 22Frank Smith, Reading Without Nonsense (New York: Teachers College Press, 1979), pp. 9, 117, quoted in Flesch, Why Johnny Still Can’t Read, p. 26. 23Flesch, Why Johnny Still Can’t Read, p. 26. 24David Chilton, review of Fire in the Minds of Men, by James H. Billington, Preface 11, 1984, p. 3. 25Mario Pei, The Story of Language (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1965), p. 90. 26Samuel L. Blumenfeld, NEA: Trojan Horse in American Education (Boise, Idaho: Paradigm Co., 1984), pp. 95, 104-107, 120. 27Ibid., pp. 104-107. 28Samuel L. Blumenfeld, The Victims of “Dick and Jane” (New Rochelle, N.Y.: America’s Future, 1982), p. 21; reprint from Reason, October 1982.

Comments for Why Not Teach Intensive Phonics?

Add A Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *