If you were to Google “learning styles,” you’d get about 15,000,000 results—maybe more by the time you read this.

Are they really THAT complicated? Where do you even begin?

Don’t worry. We’re about to dive into the three major learning styles, and you won’t even need to take a deep breath first.

What Are They?

The three major learning styles are auditory, visual, and kinesthetic—or hearing, seeing, and doing. As you can tell, they’re based on the senses.

But there’s another aspect to look at.

But there’s another aspect to look at.

At their most basic, learning styles are really learning preferences: how we prefer, if given a choice, to learn something. Since we’re all different, we all have different preferences—no surprise there!

Those with an auditory preference would rather talk through something. Those with a visual preference would rather see pictures. Those with a kinesthetic preference would rather do something hands on.

Contrary to popular belief, it’s not vital you figure out your child’s learning preference (more on that later).

But if you’re curious, read on for the simplest way.

Just thinking about how your children interact with you will show their learning preference. (Do they always want to be next to you when you read so they can see the pictures? Are they content just hearing you read? Would they rather act out the story?

Would they rather hear you explain directions, see the directions and/or pictures, or do a new task with you?)

A Word of Caution

You care that your children love to learn. You’ve sacrificed so much for them, and you’d do it all over again in a heartbeat. You love to see that sweet smile light up their faces.

And that’s how it’s supposed to be!

Because of that, it can be tempting to cater to each child’s learning preference instead of including all three in a balanced approach. In fact, some advice will even tell you to do that.

But be careful not to put your children in a learning-preference box.

What do we mean?

No one learns in just one way—God made our minds so much more capable than that!

Think back to when you learned to drive. Did you read about it and watch your parents do it, hear them tell you how, and do it yourself?

Think back to when you learned to drive. Did you read about it and watch your parents do it, hear them tell you how, and do it yourself?

Did you prefer one method of instruction over another?

Probably. But you used all three (and everyone else on the road is thankful for that!).

Jump forward to today.

If you were going to re-grout your bathroom tile, how would you learn how to do it? Listen to a podcast explaining it, watch a video showing you how (and/or read instructions with pictures), or just jump right in and do it?

Unless you’re brilliantly handy or have done something like it before, you’re probably going to use more than one method to get a handle on it.

There’s nothing wrong with knowing your child’s learning preference or incorporating more of it—not at all!

Just don’t neglect the others. Like Ecclesiastes 4:12 says, “a threefold cord is not easily broken.”

The Well-Kept Secret about Learning Styles

“You must know your child’s learning style and emphasize it for him to learn at his best.” Have you heard that, or something like it?

It’s a common view. But there’s one catch—one “secret.”

There isn’t proof.

In fact, according to Learning Styles from Nancy Chick of the Center for Teaching at Vanderbilt University, “there is no evidence to support the idea that matching activities to one’s learning style improves learning.”

The Myth of Learning Styles in Change: The Magazine for Higher Learning goes even further. According to the authors—Harvard-trained Dr. Cedar Reiner and cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham—“There is no credible evidence that learning styles exist.”

But how could the push for teaching according to learning styles be so strong without proof? Maybe there haven’t been enough studies yet?

According to Chick’s findings, “For years, researchers have tried to make this connection through hundreds of studies.”

Are the researchers just missing something?

Four distinguished college professors conducted an extensive study on the effectiveness of teaching to preferred learning styles—so extensive it takes 17 pages of small print to interpret in Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence. They were attempting to prove “optimal learning requires that students receive instruction tailored to their putative learning style.”

With their combined wisdom, insight, and years of research experience, they “found virtually no evidence.”

Learning and Individual Differences shares the results of another study by University of California faculty Laura Massa and Richard Mayer. Their findings revealed no support for the idea that visual learners and verbal learners needed different instructional methods to learn.

The idea of teaching to one learning style sounds good on the surface, but searching for a strong foundation of proof reveals there isn’t one.

What does that mean for you? Take a look at the next point.

A Word of Reassurance

Teaching using all three styles doesn’t mean you aren’t recognizing your child’s uniqueness. It doesn’t mean you’re not as committed as the mom who chooses a separate curriculum for every child according to their learning preference.

It means you’re setting your children up for success by teaching versatility. You’re showing them that they can learn no matter how the information is presented.

That means you don’t have to feel guilty about not reinventing the wheel.

You can silence the nagging doubts that you’re not doing enough unless you’re doing extra.

You can reject any thought that you’re not a great teacher because every day doesn’t include an exciting hands-on project.

You can welcome the warm security of knowing that your children, prepared to learn through each of the three styles, will have the tools to thrive in an ever-changing world of responsibility and opportunity.

How DO You Use Learning Styles?

You have the first answer—incorporate all three. If you’re using Abeka, you already are. So that’s easy.

Beyond that? Have fun!

Use your imagination, and inspire your children to use theirs. Go on field trips. Apply what they’ve learned when you’re at the grocery store, by the fish tanks at the pet store, or in your own kitchen.

If your child doesn’t like to read aloud, make it more exciting by using a robot voice, an accent, whatever!

If your child doesn’t like to write things out, give him bright pens or pencils and interesting paper.

If your child doesn’t particularly like experiments, explain how neat it is that you get to do this project and why it’s so cool. If you can, show her what it could look like when it’s done.

You’ll find that some subjects lend themselves more to one style, and that’s okay. Take art, for example. You do want to tell how to do something, and you do want to show an example. But with art, there’s nothing quite like doing.

There’s one more thing you can do: anticipate distractions.

What do we mean by that?

Here are just a few examples.

If you see that one child prefers visual learning, don’t put him in front of a window during lessons. If another child prefers auditory learning, give her headphones with classical music or ear plugs when she needs to focus in a noisy environment. If another child loves to be doing something all the time, incorporate more movement into everyday things—like jumping jacks during poetry recitation or walking around during reading time.

How You Incorporate All Three with Abeka

If you use Abeka, different ways you use each style have probably already popped into your head.

For instance, take spelling. Children see their words and write them, of course, but it doesn’t end there. They say, spell, say the word. They work with it in exercises. They play games from the lesson plans that get them moving (like by standing up on every other word or clapping with a certain letter).

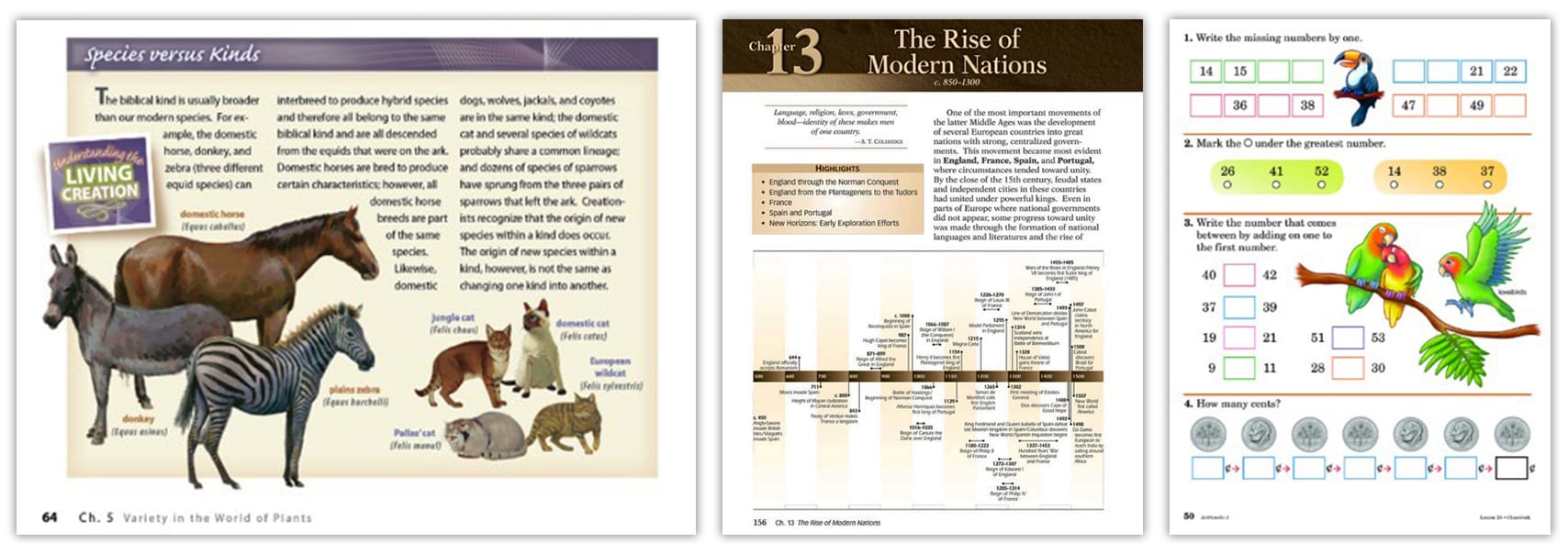

Pictures, maps, time lines, diagrams, or charts—whichever illustrates the content best—are easy to spot no matter the subject.

You use flashcards, visuals, charts, maps, and learning games. You teach songs in phonics and do oral review.

Your kids answer questions in writing and out loud. They do oral book reports and written book reports and perform poetry. They write about what they’ve read.

When they study health, they apply what they’ve learned in simple ways—like by figuring out their target heart rate or measuring how far they can stretch.

In science, they do simple experiments that don’t take special ingredients (except for high school labs), like making an earthworm farm or learning about the earth’s circumference with an apple and string.

Learning with Abeka incorporates reading, lectures, visuals, oral and written exercises, and activities—but it’s not all one thing. As the old proverb says, “Variety is the spice of life.”

When you teach with variety, you’re spicing up learning, too.

Want to see specifics on what children learn with Abeka, when, and how? It's in the Scope & Sequence.

SEE SCOPE & SEQUENCE

Comments for Learning Styles Demystified

Add A Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *